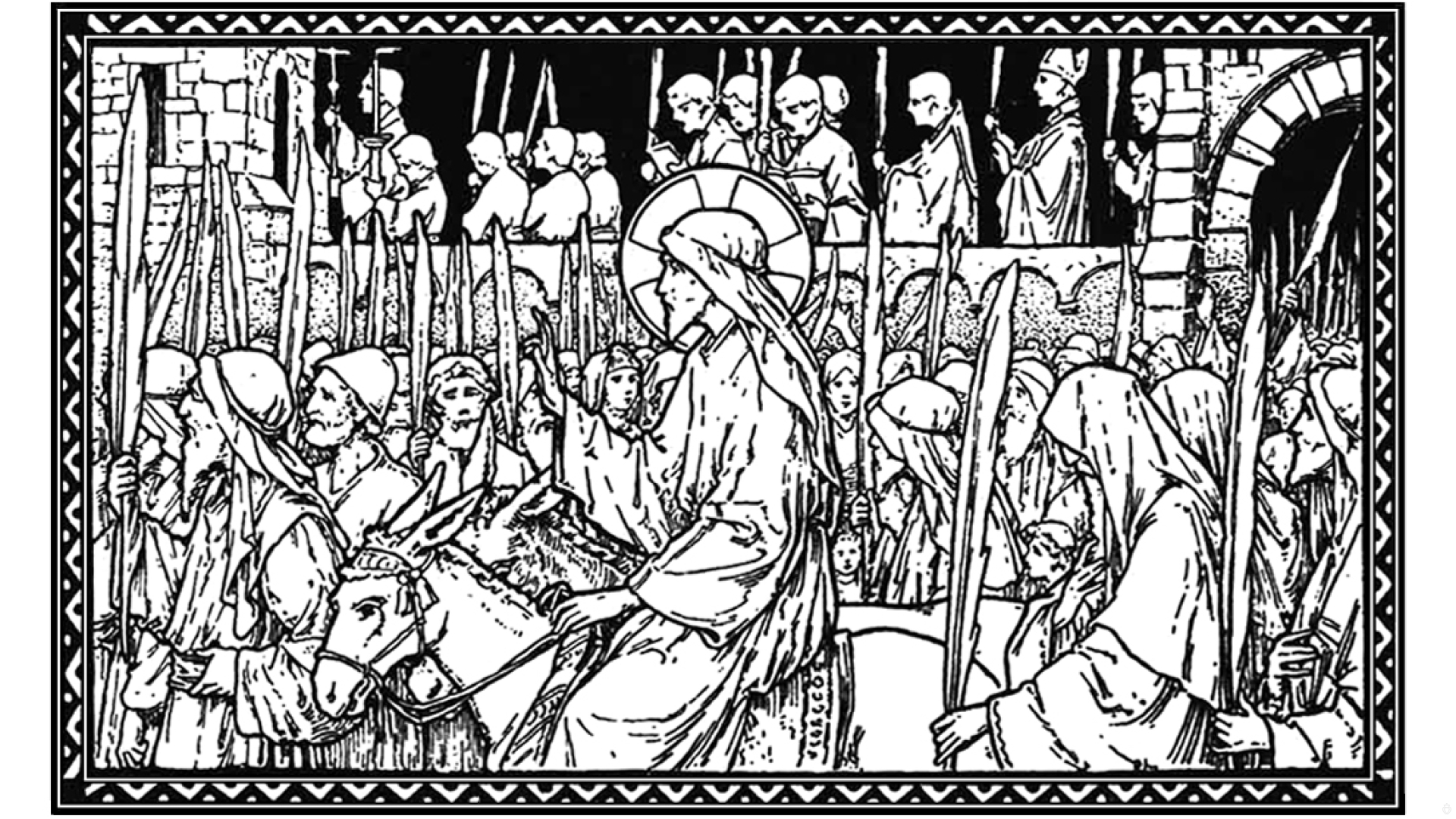

Palm Sunday - The Loneliness of Christ

The children of the Hebrews strewed their garments in the way and cried aloud, saying: "Hosanna to the Son of David." But Our Lord knew how superficial their allegiance was, how soon and how completely they were to turn against Him. And it was not only the crowd who were to desert Him, and Judas who was to betray Him: the Apostles would desert Him, too, when they fled from the garden, and Peter would desert Him, when he denied Him in the courtyard. And there are some who have seen in the women of Jerusalem a further betrayal, though of a different kind, and in His words to them they have seen a final example of that divine irony which so often masks a divine sadness. The women bewail and lament Him, but instead of giving His passion the silent support of their love and sympathy as Mary did, they obtrude their own sadness upon Him. The women are anxious, not that they should comfort Him in His agony, but that He in His agony should comfort them. Only the three Marys and John remain to give Him real companionship.

Christ’s Final Abandonment

And then upon the Cross there is the final dereliction or abandonment-expressed in the tragic lama sabachthani. William Law, the great Anglican mystic of the eighteenth century, wrote of Christ's second death, His sharing in the ultimate sense of loss which is the stuff of hell; and though this mystic departs from tradition when he identifies this final suffering with the descent into hell, we may surely accept the substance of his deep insight, and identify it rather with this cry of desolation. Christ was made sin for our sake, St. Paul tells us; and it is only to be expected that infinite Love would drain the cup to its dregs, would share in this ultimate horror, the ultimate loneliness of the soul frozen into irreparable separateness from God and from every creature.

The terrible contrast between the Gloria laus and the Passion story which follows it is a lesson in the fickle- ness of the human heart. And we in our turn are always betraying Him, always deserting Him. We betray Him from sheer superficiality and worldliness, like the crowd; we betray Him from fear like the Apostles, from greed and pride like Judas; we betray Him because of our emotional ego-centricity, as perhaps the women betrayed Him. But we forget the in- exorable fate that must then overtake us: to desert Christ is to become lonely and derelict ourselves, as Peter was lonely, as Judas was irreparably lonely.

Sharing in Christ's Dereliction

And yet there is another fact that the Saints' lives make plain to us: God calls His servants to share in His own dereliction. The mystic must pass through the dark night; for every Christian there is the dark journey to be made, either in this life or in purgatory, the crucible of fire, in the next. What then is the difference between the two derelictions, the two lonelinesses? We shall find the answer precisely in the figures of Peter and Judas. The latter's loneliness is an end, a finality: the personality can become frozen in its egoism, its pride and its greed. And to be completely frozen is to be immobile: the separateness is then irremediable because the personality has left no possible way in which life can come to it from without; it is in hell. But Peter's loneliness is not an end but a means, a means to renewal of life, because he can meet it, not with pride, but with humility. It is the whole difference between the sterility of remorse and the creativeness of contrition.

Now, God does not, of course, call us to share in His dereliction by sinning. The Saints share in that dereliction by loss and failure and defeat and heartbreak, by feeling themselves bereft of God's presence, by a universal sense of desolation. And through these things their love is purified and made perfect: they learn to cling, not to God's gifts, but to Himself, with "naked intent of the will." And So, in small ways, it can be with us; and in Lent especially we should try to make use of the disappointments and failures and sorrows that come to us, try to make them a sharing in the dereliction of the Cross, and to learn from them, from giving them back lovingly to God, how to love Him more purely and more completely.

What Sin Means

But also there is, in fact, sin in our lives; and this we should try to use as Peter used it, that out of evil good may come. Lent is again especially a time for thinking about sin-not about sins so much as about sin, deepening our understanding of what it is, what it means to God, and what it shows us of our own weakness, our need of a Saviour, but what it shows us also of the untiring patience and pity of God, who will not desert us however often we desert Him, but who on the contrary is made sin for our sake that in the end He may raise us up out of our sin and make us free.

This idea of the sense of sin as a way to humility, and so to a sharing in Christ's dereliction and a liberation from our own loneliness in His companionship and the comfort and strength which it brings-this is a recurrent theme in the Mass of today. The Introit gives us the powerlessness of man in the grip of sin and far from salvation but praying: "O Lord, remove not Thy help... look towards my defense." The Epistle gives us the key to the whole process, the trail blazed for us by Christ who "emptied Himself of His glory, taking on Himself the form of a servant and becoming obedient even unto the death of the Cross...for which cause God has also exalted Him." And so the Gradual describes how we too, if we share His sacrifice, His obedience, will share in the exaltation, God holding us in His right hand and leading us: "How good is God to Israel, to them that are of a right heart!" And in the Tract the great twenty-first Psalm, having first expressed the dereliction, goes on to proclaim the fulfillment of humanity's hopes: "In Thee have our fathers hoped: they have hoped and Thou hast delivered them; they cried to Thee and they were saved; they trusted in Thee and they were not confounded."

Remorse and Contrition

Some people are always worrying about their sins and brooding over them; that is a lack of humility and trust, and it destroys peace; it is more like remorse than contrition. On the other hand, we sometimes try to forget about our sin, to pretend that the picture is not really so black after all; and that attitude is wrong and foolish, too. We have to accept fully and unflinchingly all the evil that is in us-that is part of our dark journey-but then we have to put all that too into God's hands: it is part of ourselves, and what He wants is the whole self, just as it is. He wants us to put it all into His hands in order that He may transform it, may bring good out of the evil. If we do this-if we use the season of Lent to do this often-we shall acquire a sense of sin instead of brooding over sins, but we shall do more than that. We shall learn how sin is always estrangement, always makes us exiles from home, always makes us lonely. The best way to rid ourselves of sin, if only we were wise enough to follow it, is to deepen our awareness and love of God, our realization of our need of Him. If only we loved God enough, we should automatically be freed: the world of sin would become a strange, an alien territory, our vices would lose their power over us, our sins would fall from us like the chains that fell from Peter in prison. But we are very blind; and we need to share in Christ's dereliction in order that we may come to see.

Sin Begets Estrangement

And there is something else that we can learn. When Adam and Eve had sinned, they saw that they were naked: not naked like the mystics who follow the naked Christ and, having nothing, possess all things, but bereft and lonely like the forlorn figure of Judas, an empty shell swinging on a gibbet. Sin always estranges; and to share sin, recognized as such, always estranges the sinners: at a superficial level a connivance may seem an added bond between them, yes, but deeper down it is a division, a barrier, between them. And omnes nos peccavimus: we all share in the sin of the human family; and so we are estranged from one another, and being estranged we fear one another, and fear begets strife. So it is that individuals regard one another as rivals, as potential menaces, and so they fear one another, and because of their fear they try to hurt one another. So it is that nations think they are menaced by other nations, and their fear in the end produces war. And the only way to cure the fear is to cure the loneliness, and the only way to cure the loneliness is to cure the sin which produces the loneliness; and the cure of sin is sacrifice.

So, if we use the season of Lent to deepen our sense of sin and to turn our sin into the material of sacrifice, we are working not for ourselves alone: we are helping to save humanity by helping in however small a way to re- store the family life of humanity. To think of the scene on Calvary is to see that family life reduced to the few still figures standing at the foot of the Cross, while all around them is the chaos and tumult and confusion of men who have lost God and are derelict and-as we so often do-are making a great noise in order to try and forget the fact. But to join in Christ's so different dereliction, to join the tiny group at the foot of the Cross-but a group swelled now by all those who have loved Him and joined Him through the Church's history-that is to unite with Him and them in re- placing hatred by love and fear by friendship and discord by peace.

Let us, then, throw down our garments at His feet, not as the children of the Hebrews did in a volatile superficial enthusiasm, but as Francis did: let us give Him during Lent things that are costly to us, but, behind and deeper than all that, give our lives into His hands. Then indeed we can sing: "Hosanna to the Son of David!" We can sing: "Glory, praise and honor be to Thee, Christ our King." And in the majesty of that kingship, which is also the lowliness of a human companion- ship, we can find our own wounds of loneliness healed, and being ourselves renewed can lead others to that healing and renewal in their turn.